"All models are wrong, but some are useful."

All models simplify the complexity of reality.

6/18/20254 min read

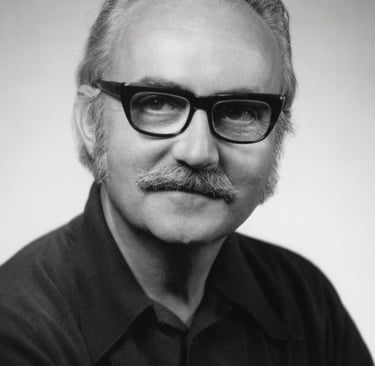

The statement "All models are wrong, but some are useful" is a cornerstone aphorism in statistics and science, famously coined by the British statistician George E. P. Box. It encapsulates a fundamental truth about our attempts to understand and predict the world: no model can ever perfectly replicate reality, but models can still be incredibly valuable tools.

This might seem paradoxical. How can something inherently flawed be useful? Understanding this quote requires delving into the nature of models and the purpose they serve.

Why Are All Models "Wrong"?

A model, in this context, is any simplified representation of a system or process. This could be a mathematical equation, a physical scale model, a computer simulation, a diagram, or even a mental framework. Models are inherently "wrong" – or perhaps more accurately, incomplete – for several reasons:

Simplification: Reality is infinitely complex. To create a manageable model, we must simplify, omit details, and make assumptions. A map leaves out individual trees; an economic model might assume perfectly rational actors; a weather model simplifies atmospheric physics. This simplification is necessary but means the model deviates from the full complexity of the real world.

Assumptions: Every model rests on underlying assumptions. These assumptions might hold true most of the time or only under specific conditions. When reality deviates from these assumptions, the model's accuracy suffers.

Limited Scope: Models are usually designed for a specific purpose or context. Applying a model outside its intended scope can lead to inaccurate or misleading results. Newton's laws of motion are incredibly useful for everyday physics but break down at relativistic speeds or quantum scales.

Data Limitations: Models built from data are only as good as the data they are trained on. Incomplete, biased, or noisy data will lead to flawed models.

Why Are Some Models "Useful"?

Despite their inherent imperfections, models provide immense value:

Understanding: Models help us distill complex systems into more understandable components. They allow us to identify key relationships, variables, and dynamics that might otherwise be obscured. The Bohr model of the atom, while technically inaccurate by modern standards, was crucial for understanding atomic structure.

Prediction & Forecasting: Models allow us to make educated guesses about future outcomes or behavior under different conditions. Weather forecasts, financial projections, and epidemiological predictions are all based on models. While never perfectly accurate, they provide crucial guidance for planning and decision-making.

Decision Making: Models help evaluate the potential consequences of different actions or scenarios. Businesses use financial models to assess investment opportunities; engineers use simulations to test designs before building prototypes.

Communication: Models provide a common language and framework for discussing complex ideas. Diagrams, flowcharts, and graphs help convey information efficiently.

Testing Hypotheses: Models allow us to explore "what if" scenarios and test hypotheses in a controlled environment without manipulating the real world directly.

Practical Application Tips: Using Models Wisely

The wisdom of Box's quote lies in how we approach using models. It encourages critical thinking and humility. Here are some practical tips:

Acknowledge Limitations: Never treat a model as absolute truth. Always be aware of its underlying assumptions, simplifications, and the scope for which it was designed. Ask: What is this model leaving out? Under what conditions might it fail?

Focus on Purpose (Fit-for-Purpose): The primary criterion for a model is not its perfect accuracy, but its usefulness for the specific task at hand. Is the model helping you understand, predict, or decide better than you could without it? Is its level of accuracy sufficient for the decision you need to make?

Validate and Iterate: Whenever possible, test your model's predictions against real-world data. Be prepared to refine, update, or even discard models as new information becomes available or the system changes. Models are not static artifacts.

Use Multiple Models: Complex problems often benefit from multiple perspectives. Different models, even if individually flawed, can highlight different aspects of a system. Comparing results from several models (triangulation) can lead to more robust insights.

Communicate Uncertainty: When presenting results from a model, be transparent about its limitations and the associated uncertainty. Avoid presenting point estimates as certainties; use ranges, confidence intervals, or scenario analyses where appropriate.

Prioritize Parsimony (Keep it Simple): While adding complexity can sometimes improve accuracy, it can also make a model harder to understand, validate, and use. Start simple and only add complexity if it significantly improves the model's usefulness for its intended purpose (often related to Occam's Razor).

Examples in Practice:

Weather Forecasts: We know the 7-day forecast won't be perfectly accurate, especially further out. Temperature predictions might be off by a few degrees, and the exact timing of rain can shift. Wrong? Yes. Useful? Absolutely. It helps us decide what to wear, plan outdoor activities, and prepare for severe weather. We use it because it's useful for those decisions, despite its known imperfections.

Economic Models (e.g., Supply & Demand): These models simplify complex human behavior and market dynamics. They rarely predict exact prices or quantities. Wrong? Yes, in their precision. Useful? Yes, for understanding fundamental relationships – how price generally responds to scarcity, how taxes might impact consumption, etc. They guide policy and business strategy.

Climate Models: These complex simulations project future climate scenarios based on greenhouse gas emissions. They involve many assumptions and simplifications of Earth systems. Wrong? The precise degree of warming or sea-level rise by a specific date has uncertainties. Useful? Critically. They provide the best available understanding of long-term trends and potential risks, informing global policy on emissions reduction and adaptation strategies.

Conclusion:

George Box's famous quote is not a dismissal of modeling, but a call for informed and pragmatic use. It reminds us that models are tools, not oracles. By understanding their inherent limitations and focusing on their specific purpose, we can harness their power to gain insights, make better predictions, and navigate a complex world more effectively. The goal is not perfect representation, but practical utility. Embrace the imperfection, understand the assumptions, and use models wisely – for that is where their true value lies.